A global consensus seems to be forming that an artificial intelligence (AI) system does not deserve—at least for now—to be named as an inventor on a patent application. The question is under consideration and being settled in most of the major countries where patents are sought. The UK Supreme Court (in Thaler v. Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks), similar to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (in Thaler v. Vidal), recently held that the governing patent statutes require that the inventor be a natural person. While we can all rest a little easier with this issue put to bed, the question is for how long. In the US, the Federal Circuit left open the question of whether an invention assisted by AI would be patentable. AI is not going away, and when someone eventually pairs a quantum computer with a large language model, the field of generative AI is likely to explode in ways we cannot imagine.

The issue of inventorship can be complicated, as the above court cases show. In addition to these cases, the recently issued Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions (the Guidance) from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) provides additional issues to consider. While the Guidance is helpful, it is important to remember that this is not law and it is unclear how or whether future courts will be persuaded by the USPTO’s thoughts on inventorship.

Patenting issues involving software historically were related to patents directed to the software itself. With AI tools becoming more prevalent, the issue of patentability of inventions in which the purported inventor used AI should now be a consideration for all patent practitioners to consider. How will we know whether an invention that an AI system helped or assisted in conceiving will be patentable?

The validity of patents involving software has been evolving for the past 50 years. Previously, the issues focused on patentable subject matter and the abstractness of software inventions. The new generation of AI-based tools are creating new challenges for patent applicants and their counsel. Patenting is a long game. Thus, the success of future litigation, including that involving inventorship, may be won or lost based on the wording of applications currently being drafted. Therefore, the time to anticipate these issues is today. What follows is a discussion of how to fortify patents resulting from the contributions of AI systems against inventorship challenges that may not arise until the patent is litigated, possibly years from now. As discussed in the Guidance, one possible answer may be found using the factors outlined by the Federal Circuit in Pannu v. Iolab Corp.

In Pannu, the Federal Circuit laid out a three-part test to determine inventorship. To be named as an inventor, one must prove that they: (1) contributed in some significant manner to the conception of the invention; (2) made a contribution to the claimed invention that is not insignificant in quality when that contribution is measured against the dimension of the full invention; and (3) did more than merely explain the real inventor’s well-known concepts and/or the current state of the art.

Recently, the Federal Circuit considered the issue of inventorship in two separate cases, HIP, Inc. v. Hormel Foods Corporation and Blue Gentian, LLC v. Tristar Products, Inc. In both disputes, whether someone was an inventor came down to whether their contribution was “significant” and what constitutes an idea being “significant.”

In the first case, the parties worked together in developing a process for making “precooked” bacon that just needs to be reheated. As part of the development process, the parties entered into an agreement to jointly develop an oven to partially cook the bacon. At a certain point, Hormel moved the oven and the development process in-house. Later, Hormel developed a two-step process that included microwaving the bacon. The lower court found that the HIP inventor made a significant contribution to one of the claims. On appeal, however, the Federal Circuit, relying on the Pannu factors, provided an extensive analysis of the alleged joint inventors’ contributions. Relevant to this discussion, the Federal Circuit held that even though the HIP inventor’s idea was claimed, the contribution was insignificant under the second Pannu factor.

In Blue Gentian, the invention in question related to an expandable garden hose. The dispute was whether Blue Gentian’s Michael Berardi or a nonparty to the proceedings, Gary Ragner (a licensor to Tristar Products), should be the named inventor. Before the filing of the patent, Berardi, the purported inventor of the patent in question, and Ragner, who had designed and created an earlier-invented expandable hose, met. At the time of this meeting, the patent applications filed by Ragner (who has a master’s in aerospace engineering) were not published and Berardi (who has a degree in sociology) did not know how to design the expandable hose. The prototype shown by Berardi at the meeting used a coil spring to retract the hose. There was some conflicting testimony, but Ragner appeared to have told Berardi that his earlier prototypes used surgical tubing and he intended to use an elastomer. Less than three months later, Berardi filed a patent application that included a claim limitation that the inner layer of the hose included an elastic material. The district court found that Ragner was an inventor and ordered the correction of inventorship. The Federal Circuit agreed.

Both cases were highly fact-dependent, and we expect that future inventorship disputes involving the use of AI systems will also be fact-dependent. Whether the natural person is an inventor may come down to what portions of the claimed invention the natural person conceived and which the AI system generated. This situation may play out in ways we cannot imagine at this point given the myriad fact patterns that could arise. This uncertainty could be unsettling to those developing products, or their investors, who have traditionally been able to look to intellectual property laws to protect their investments. But how do inventors keep their competitors from copying their inventions? While there are currently no silver bullets, there may be ways to patent inventions that include AI-generated content that shows significant contribution by a natural person.

The combination of prior-art (old) components when combined in a new way may be patented (KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc.). A logical extension of this rule is that when components are not patentable in and of themselves (such as a module completely generated by an AI system), these inventions may be patentable when combined together in a new and nonobvious way. For example, a software engineer executes an AI program to generate modules of software, A, B, and C or uses AI-generated modules from a library:

The engineer then combines these modules in a new way that provides a technical advantage or benefit, such as making the computer execute a routine faster or use less memory/bandwidth.

If this new combination of modules provides an unexpected benefit (to overcome obviousness rejections), the AI-generated content should be patentable as a combination. Depending on the facts surrounding conception and how the AI tool was utilized, the natural person’s contribution of combining the modules in this way may be sufficient to satisfy the Pannu factor that the inventor’s contribution is significant. This could be true even if the individual modules were not patentable because they were solely generated by an AI system.

The patenting of prior-art components that are combined in a new way is a situation that often arises in the electromechanical arts, particularly when an inventor is trying to improve an existing product. In these situations, patent attorneys have often counseled clients to review the interfaces between the old components, or the old and new components, to evaluate the changes made to adapt the components to work together. Similarly, the interfaces between the components should be reviewed to see whether they are new and nonobvious. Often, it is these interfaces that allow the combination of prior-art components to be patented, and more importantly, they provide commercial value to the product incorporating the invention.

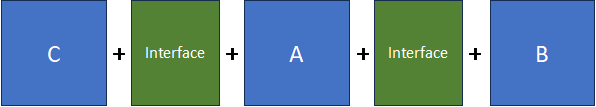

In many cases, AI-generated content may not be a thing in and of itself but rather is a combination of AI and non-AI content with interfaces:

Here, the interfacing of the AI-generated/prior-art modules A, B, and C may be new and nonobvious. Or the interfaces themselves may be patentable. While these claims may be narrower than desired, they may provide a level of protection that prevents others from directly copying the product. Further, the natural person’s contribution of combining these components may be sufficient contribution to satisfy the second step of Pannu and allow a patent to withstand a challenge to its validity.

Much like the early days of patent drafting after the US Supreme Court’s decision on the test for patent eligibility under Alice v. CLS Bank Int’l, it may be advisable to incorporate additional supporting wording into the application, such as passages about the advantages of the combination of the interfaces when dealing with AI-generated content, so as to anticipate potential inventorship issues.

The Guidance provides a framework for examiners to consider whether the natural person is an inventor. However, it will be rare when sufficient information is presented to cause the examiner to make such a challenge to the applicant. Because the USPTO is unlikely to challenge the inventorship asserted by an applicant, these inventorship issues will likely not be raised until patent litigation. As a result, consider including a set of claims to the interfaces now, at least in dependent claims, to provide insurance in protecting the validity of the patent when infringement occurs five, 10, or more years from now. Further, these inventorship issues may be raised not just in software but in any invention where AI-based tools are used.