On August 29, 2023, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Assistant Secretary for Health, Rachel Levine, sent a letter to US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Administrator and former Attorney General to the State of New Jersey, Anne Milgram, requesting that the agency remove marijuana (cannabis) from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). Under this new HHS recommendation, cannabis would be rescheduled under Schedule III, a less restrictive DEA classification, which would ease certain federal regulatory burdens hindering cannabis research and likely spur industry growth in states that have legalized medical and/or adult-use cannabis.

This move reflects a significant demonstration of the Biden administration’s positively evolving policy view on the federal approach to cannabis and comes nearly 10 months after President Joe Biden’s initial request for a federal review of cannabis scheduling.

Background

Since the 1970s, the DEA has scheduled cannabis under the Schedule I classification, alongside heroin and LSD, as a drug “with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” However, the national cannabis regulatory landscape has changed significantly over the past decade, with 23 states and Washington, DC, having legalized recreational adult-use cannabis and 38 states having legalized medicinal-use cannabis.

Under the CSA, substances are categorized based on their medical utility and potential for abuse.

- The DEA defines Schedule I substances as drugs with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”

- The DEA defines Schedule III substances as drugs with “a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence.”

Both Schedule I and Schedule III substances are federally prohibited for possession, distribution, and manufacturing without a valid prescription or the necessary DEA registration, with varying degrees of legal consequences. The penalties for trafficking Schedule I substances are the most severe among all categories of controlled substances, carrying sentences of up to 15 years of imprisonment and fines reaching up to $250,000. In contrast, distribution or possession with intent to distribute a Schedule III substance carries a maximum sentence of five years’ imprisonment and fines of up to $15,000.

Although scheduled under the CSA, Schedule III substances are less regulated than their Schedule I and Schedule II counterparts. To that end, the most significant impact of rescheduling cannabis as a Schedule III substance would be the easing of restrictions regarding—and likely expansion of—national research opportunities. For example, as a Schedule I substance, cannabis is generally deemed inappropriate for research studies involving human subjects, even under certified medical supervision.

In the past, there have been a number of requests to reschedule cannabis’ federal designation, including two attempts under the Obama administration. Two Democratic governors, Governor Gina Raimondo of Rhode Island and Governor Jay Inslee of Washington, petitioned the federal government to reconsider its treatment of cannabis and related DEA classifications. In 2016, the Obama administration denied both bids, citing concerns that cannabis has a high potential for abuse, has no accepted medical use in the United States, and lacked an acceptable level of safety even under medical supervision.

While states may continue to grow and incentivize investment within in-state cannabis industries, the Biden administration’s recent recommendation to reschedule cannabis marks a new and significant shift in federal cannabis policy sentiment.

The Rescheduling Process

The process of rescheduling cannabis to a Schedule III substance involves several steps:

- Initiation of a review by the DEA, HHS, or a public petition.

- The DEA asks HHS to evaluate the medical and scientific evidence concerning a drug’s scheduling.

- HHS, through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), conducts a comprehensive analysis of the drug and its schedule based on eight factors, including its potential for abuse and medical use.

- HHS makes a schedule recommendation based on the scientific evidence.

- The DEA conducts its independent review, considering HHS’s determination and additional relevant data.

- The DEA establishes the final schedule.

Before HHS arrived at its Schedule III recommendation and formal request to the DEA, the FDA first had to conduct a rigorous scientific and medical evaluation. Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. 811(b) of the CSA, this evaluation applied an “eight-factor analysis,” taking into account factors such as the drug’s potential for abuse, its history of misuse, and the scientific evidence of its pharmacological effects.

At the conclusion of its evaluation, the FDA then forwarded its results to HHS, which ultimately informed Assistant Secretary Levine’s formal recommendation to DEA Administrator Milgram.

The DEA has historically maintained the position that the United States is obligated to classify cannabis as either Schedule I or Schedule II under the CSA.

The rescheduling of cannabis is undeniably a historic development. Now that Milgram has acknowledged receiving the HHS recommendation, the DEA is expected to initiate an independent review process. Typically, this process involves a public comment period followed by the publication of a final regulation in the Federal Register, complete with responses to comments and explanations for any revisions made. This formal rulemaking procedure necessitates that the DEA conduct a public hearing on the record, at which time evidence would be presented to the DEA regarding the accepted medical use of cannabis and the risk of cannabis misuse.

A DEA administrative law judge, or potentially a panel of DEA judges, is then responsible for rendering a decision on cannabis’ scheduling, ultimately shaping the final regulation that is published in the Federal Register. Of course, all final regulations remain susceptible to legal challenges and judicial review within the federal court system. At this time, any next steps and decision-making authority are within the jurisdiction of Milgram and the DEA.

Potential Effects of Cannabis Reclassification

Reducing Enforcement Risks: For the past several years, the federal government has adopted a “nonenforcement” position with respect to cannabis-related activities occurring within states where such activities are authorized by state law. This position, however, is not required by law and, notably, is subject to change based upon variations of policy across political administrations. Thus, should the DEA act on HHS’s recent recommendation and initiate a cannabis rescheduling process, it would represent formal, administrative action to reinforce the federal government’s current nonenforcement position with respect to state-regulated cannabis markets. This change should further engender confidence from state markets that this evolving federal perspective will continue to inform future federal cannabis policy.

Financial Services and Institutional Lending: While rescheduling cannabis to Schedule III would not entirely resolve the cannabis industry’s difficulties in accessing institutional lending and traditional financial services, it may prompt some financial institutions to revisit their internal risk calculations underlying those policies. It also bears noting that this past April, a group of bipartisan lawmakers including Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), Sen. Steve Daines (R-Mont.), Rep. Dave Joyce (R-Ohio), and Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) reintroduced the Secure and Fair Enforcement Banking Act, or SAFE, which would remove this burden entirely. On September 6, 2023, after Congress returned from August recess, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer reiterated his commitment to advancing SAFE, while highlighting the arduous road ahead for any federal cannabis legislative reform and the necessity of bipartisan cooperation.

Tax Policy: Although cannabis rescheduling does not automatically legalize state-legal cannabis programs, it would likely remove tax constraints imposed by Section 280E of the IRS tax code. This provision currently prohibits state-authorized cannabis businesses from claiming traditional deductions (and reducing their tax liability) due to cannabis’s current status under the CSA. Reclassifying cannabis would exempt it from an IRS rule that denies tax deductions to businesses engaged in controlled substance “trafficking.” Currently, cannabis businesses face tax rates of up to 70 percent due to their federal status, subjecting them to tax code restrictions on deductions for expenses like salaries and benefits. This limitation would no longer apply under the Schedule III classification. If the DEA ultimately reschedules cannabis, cannabis businesses nationwide would indeed see a substantial reduction in federal taxes.

Criminal Justice Reform: Rescheduling cannabis could bring about a significant reduction in penalties for cannabis-related offenses under federal law. This change not only eases the legal burden on individuals involved in the cannabis industry but also serves as a potential catalyst for policy reforms in states where cannabis remains illegal. Advocates for cannabis legalization in states on the verge of legislation, such as Ohio, Minnesota, and Hawaii, can leverage this opportunity effectively in their efforts to advance legalization in their respective state legislatures.

Potential to Lawfully Prescribe Cannabis: In the event cannabis is successfully rescheduled per Assistant Secretary Rachel Levine’s August 2023 recommendation, cannabis would occupy the same scheduling category as drugs like ketamine, testosterone, and anabolic steroids. Schedule III drugs can be obtained with a prescription, which may not be filled more than six months after its issuance date or more than five times total unless renewed by a practitioner.

Currently, in states with medical cannabis programs, doctors offer “recommendations,” not prescriptions—this is due to discrepancies between federal and state medicinal cannabis laws that the American Medical Association’s Journal of Ethics has discussed at length. Clinical practitioners risk violating federal law when seeking to provide their patients with medicinal cannabis, which does carry the risk of the DEA revoking a clinician’s medical license. Even in states where cannabis is legal—for medicinal purposes or otherwise—prescribing a Schedule I substance would constitute aiding and abetting the acquisition of an illegal substance, which could result in revocation of DEA licensure or possible imprisonment. However, in states with legalized medicinal cannabis programs, doctors write “recommendations” for eligible cannabis patients. This recommendation loophole was upheld by the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Conant v. Walters, which decided that a physician discussing the potential benefits of medicinal cannabis and making such a recommendation constitutes protected speech under the First Amendment.

Still, this practical distinction remains an impediment to concerned clinicians. For example, the American Medical Association has previously noted that physicians in Massachusetts have been slow in writing medical cannabis “recommendations” for patients, in part due to visits from DEA agents to physicians involved with cannabis dispensaries. Cannabis reclassification would greatly empower certain ethical considerations within the clinical community when directing patients toward treatment plans inclusive of cannabis therapies—and potentially boost a number of sectors throughout the medicinal cannabis industry.

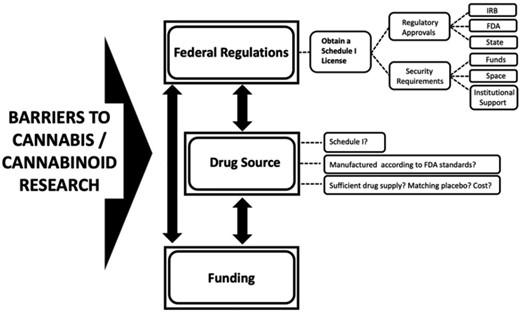

Expanded Research: In the past, conducting credentialed research studies with cannabis has been exceedingly challenging due to federal regulations mandating a permit from the DEA. Researchers have expressed frustration over these limitations, which force them to obtain cannabis solely from a single facility at the University of Mississippi—a crop that differs significantly from the high-potency products available in state-legal markets. The Biden administration has already begun to enact policy aimed at strengthening national cannabis research opportunities; in 2022, President Biden signed the Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act, aiming to broaden opportunities for manufacturing and researching marijuana.

Should the DEA reschedule cannabis as a Schedule III substance, the expansion of further authorized clinical studies may follow—as well as further capabilities for cannabis use in the health and wellness sectors.

Industry Investment: HHS’s recommendation has already led to substantial stock price increases for publicly traded cannabis companies. Moreover, any policy change that reduces legal and regulatory uncertainty at the federal level also serves to reduce overall risk of entering lawful state cannabis markets. As stated, rescheduling cannabis would have a profound impact on pharmaceutical, technology, research, political, legal, and other industry sectors—reduced risk is likely to attract more investors to these markets.

Political and Social Considerations

The timing of HHS’s recommendation holds political significance, occurring just before midterm elections and coinciding with the 2024 presidential election cycle. Assistant Secretary Rachel Levine’s August 2023 letter to DEA Administrator Anne Milgram follows President Biden’s fall 2022 directive to review cannabis classification approximately. The duration of the DEA’s public review process remains uncertain.

Cannabis stakeholders may note the Biden administration’s significant political investment in federal cannabis policy reform.

- In May 2021, the DEA approved licensed facilities to grow cannabis for the purpose of medical research for the first time since 1968.Prior to this, the University of Mississippi was the only institution in the United States legally permitted to grow the plant for that use. Previously, in 2016, an application process was put in place for research growers, but no applications were later approved under the Trump administration.

- In October 2022, Biden announced a mass pardon for past federal cannabis possession convictions, encouraged governors to do the same for state cannabis possession convictions, and instructed Attorney General Merrick Garland and Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra to review the classification schedule of cannabis, which could result in the removal of cannabis from Schedule I of the CSA.

- On December 2, 2022, Biden signed the Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act. This law is the first stand-alone cannabis-related bill approved by both chambers of the US Congress.

Polls indicate that a majority of Americans support legalization, with 68 percent of adults favoring it. Although demographic and partisan differences persist, both political parties seek to capitalize on the benefits of easing cannabis restrictions.

Conclusion

HHS’s recommendation to reschedule cannabis to Schedule III marks a significant milestone for the cannabis industry. Nevertheless, any federal cannabis policy reform will see a long road ahead. McCarter & English’s Cannabis and Government Affairs Practices are well positioned to navigate this critical juncture, possessing a deep understanding of cannabis issues and valuable connections, including with the head of the DEA, former New Jersey Attorney General Anne Milgram.

Appendices

| Schedule I |

| Schedule I drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Some examples of Schedule I drugs are: heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana (cannabis), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy), methaqualone, and peyote. |

| Schedule II |

| Schedule II drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a high potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous. Some examples of Schedule II drugs are: combination products with less than 15 milligrams of hydrocodone per dosage unit (Vicodin), cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), meperidine (Demerol), oxycodone (OxyContin), fentanyl, Dexedrine, Adderall, and Ritalin. |

| Schedule III |

| Schedule III drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Schedule III drugs’ abuse potential is less than that of Schedule I and Schedule II drugs but more than that of Schedule IV. Some examples of Schedule III drugs are: products containing less than 90 milligrams of codeine per dosage unit (Tylenol with codeine), ketamine, anabolic steroids, and testosterone. |

| Schedule IV |

| Schedule IV drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a low potential for abuse and a low risk of dependence. Some examples of Schedule IV drugs are Xanax, Soma, Darvon, Darvocet, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien, and Tramadol. |

| Schedule V |

| Schedule V drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a lower potential for abuse than those in Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. Schedule V drugs are generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes. Some examples of Schedule V drugs are: cough preparations with less than 200 milligrams of codeine per 100 milliliters (Robitussin AC), Lomotil, Motofen, Lyrica, and Parepectolin. |